US election: The changing role of Uncle Sam

American voters have chosen a new direction, but what impact do presidents really have? We uncover the long-term trends moving the world’s biggest economy.

5 min read

Become A Client

When you become a client of Coutts, you will be part of an exclusive network.

After days of vote counting, the result is in: the US electorate has decided a change in direction is needed and handed Joe Biden the keys to the White House.

All presidents seek to put their own stamp on a country. But the impact they have on the economy and – by extension – investment markets can be limited by the tectonic forces of demographic change and the global economy.

We asked Alan Higgins, our UK Chief Investment Officer, and James Rose, Coutts Wealth Manager and a self-confessed ‘US politics geek’, for their views on what the change in presidency means for the long-term prospects of the US.

PRESIDENTS DON'T MOVE MARKETS

Alan Higgins:

Particularly before an election, market commentators will declaim on the market impact of, for example, tax rates and the level of corporate regulation on equity markets. Our view is that while these are important subjects, equity returns are a product of deeper corporate and economic factors. We’re likely to see markets shift around a bit as investors get used to the idea of a new president, but the underlying drivers of investment returns will reassert themselves.

Joe Biden’s desire to increase corporate taxes is well publicised. He may yet be curtailed by a Republican-dominated Senate – a final run-off in Georgia in January will decide if they retain control – but the impact of tax rises for investors is generally overstated.

Taxes were raised by, among others, Presidents Truman, Clinton, George W Bush and Obama. Each time, after a period of adjustment, markets trended back in line with prevailing corporate fundamentals.

The Clinton-era tax rises provide an especially important comparison. The prevailing thinking then was concern about budget deficits and overall debt levels. The act that brought in the tax rises was even called the ‘Deficit Reduction Act of 1993’.

In 2020 this kind of thinking seems quaint. Few major OECD countries worry much about government debt levels now, despite a substantial increase over the last 30 years – US debt as a proportion of GDP was around 60% in 1993; it now stands at 107%.

“Crucially, markets will be looking at how President Biden deals with the COVID-19 pandemic.”

But back then interest rates were much higher – the US 10-year bond yield was touching 8% in 1993. Today, the US Federal Reserve Reference Rate is 0-0.25% and real yields for US government bonds – based on prices for bonds traded on the market – are below zero in some cases.

This is an important distinction, as the difference in rates made it much more expensive to pay for government spending in the 1990s. Not only was there the initial expenditure, but regular payments on the bonds issued to pay for it were much, much higher.

Low interest rates mean that Biden’s tax increases would be shared in the economy, fuelling economic expansion. This is an advantage Clinton never had: his tax rises were aimed at reducing the cost of government debt and a lower proportion of the extra cash ended up contributing to growth.

Moreover, the market impact of Clinton’s tax rise was short term. In fact, the stock market went on to rise by over 70% in both Clinton eras, much higher even than the return during the Reagan-era boom.

Crucially, markets will be waiting to see how President Biden deals with the COVID-19 pandemic. In the immediate term after he takes charge, markets will be looking at what support the government will offer.

The parties in the House of Representatives and the Senate have been negotiating for some time, and the scale and timing of a relief package will be far more significant for markets than Biden’s tax plans. Upcoming vaccine trial results will also be closely watched by investors, as we’ve seen from the market reaction to Pfizer’s announcement of successful results this week.

AMERICA'S CHANGING ROLE ON THE WORLD STAGE

James Rose:

President Trump’s ‘America first’ approach has led to a retreat from international collective action on global issues, and a ‘zero-sum’ view of international politics: in all relationships there must be winners and losers, and if you are not obviously winning, then you must be losing.

The question is whether this is an aberration of the Trump presidency or part of a broader trend for a more insular US?

The Biden victory is likely to see re-engagement with global politics at least in the short term – for example, ending the process of the US leaving the World Health Organisation. We should also see a broader return to liberal multilateralism, for example re-joining the Paris Climate Accord and the Iranian Nuclear deal. We think this would help to re-establish America’s influence on long-term global policy.

But US presidents in the coming years will also have to address an increasingly powerful and assertive China.

A key element must be to invest domestically. America will need to better equip itself for a world where not only business, but also warfare, are increasingly being done online. Domestic policy, therefore, will be just as important as foreign policy in building a US that is strong and forward-facing to the world. The question is whether President Biden can get the balance right and set the country on a clear path for others to embed long into the future.

An increasingly multi-polar global economy

Alan Higgins:

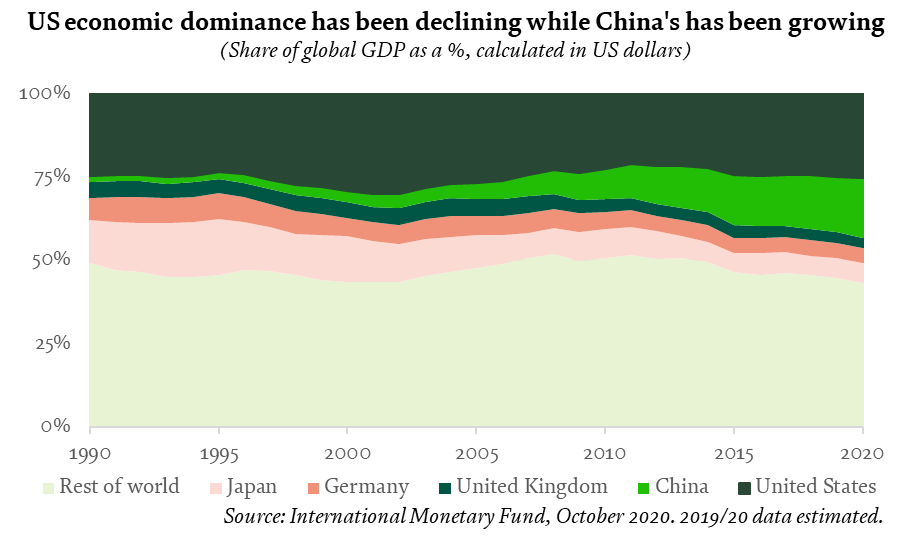

While the political role of the US is to a large extent a matter of choice for its body politic, its influence on the global economy has been gradually eroding. Simultaneously, China’s share has expanded considerably.

Why? Two reasons: globalisation and aggressive economic development in China.

America of course has historically been one of the main proponents of globalisation. Low barriers to trade, and freedom of movement for capital have been key planks of economic policy in the capitalist west since the 1980s.

More surprising is the enthusiasm and success of communist China in this context. But China has been undergoing massive political and economic change. Its overarching economic system is often referred to as ‘state capitalism’ where commercial corporations are largely owned by the state, although there has also been substantial relaxation of rules around private ownership of business.

China’s burgeoning economic power has also fuelled its ‘Belt and Road’ initiative, building a global trading network through investment in primarily developing countries across the world. In the longer term, China’s investment in developing and frontier economies in Africa, for example, could substantially increase its economic and political clout, further reducing the influence of the US.

CHANGES TO THE SUPREME COURT COULD HAVE LONG-LASTING IMPACT

James Rose:

One of the key areas of President Trump’s legacy will be his impact on the US Judiciary, and in particular the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court judges have lifetime tenure, meaning that, once appointed, they can only realistically be removed by resignation or death. President Trump was able to appoint three new Supreme Court Justices, the most of any president since Reagan, locking-in a conservative majority on the court.

This could stand in the way of progressive policy goals for decades to come and have a substantial impact on how the US is governed.

The options for challenging this are limited. The number of Supreme Court justices is not set by the Constitution. President Biden could seek to ‘pack the court’ – simply increase the total number from nine to, say, 15 and appoint liberal-leaning justices to the new position, as Franklin Roosevelt once threatened to do.

Aside from the political difficulties of getting such a move past a Republican Senate, it’s a decidedly unpopular policy among the American people as a whole. It would likely damage the Democratic party’s credibility and Biden has previously spoken out against this idea. However, he has been noticeably silent on the subject since Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death, meaning it may be being considered.

Alan Higgins:

One of the first cases to come before the court after the election will be a ruling on the Affordable Care Act, which extended health insurance to many American citizens who had previously been excluded from coverage. As a key policy of the Obama-Biden administration, this will also be a vital issue for President Biden.

Further out, the new president’s plans covering, for example, the transition to a low carbon economy could also face legal challenges. A conservatively biased Supreme Court could block these plans.

But people-power can express itself in other ways. Many companies are adopting sustainable practices based on the demands of consumers and shareholders, regardless of government policy. It’s possible that a similar alignment of interests could drive change in other areas.

When investing, past performance should not be taken as a guide to future performance. The value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up, and you may not recover the amount of your original investment.